Central to the greatness of Saudi Aramco are the talented and dedicated people upon whose shoulders the company has been built. Over the years, tens of thousands of Aramcons—Saudis and ExPats alike—have made manifold contributions to the company’s success. Along the way, they have forged enduring bonds of friendship and mutual understanding among themselves, setting a powerful example for others in future years to follow. Tom Barger, Aramco president and CEO in its early days, personified these qualities. Tim Barger, Tom’s son, learned at his father’s feet and followed in his footsteps, honoring his example while adding notably to the ever-unfolding Aramco story with worthy contributions of his own.

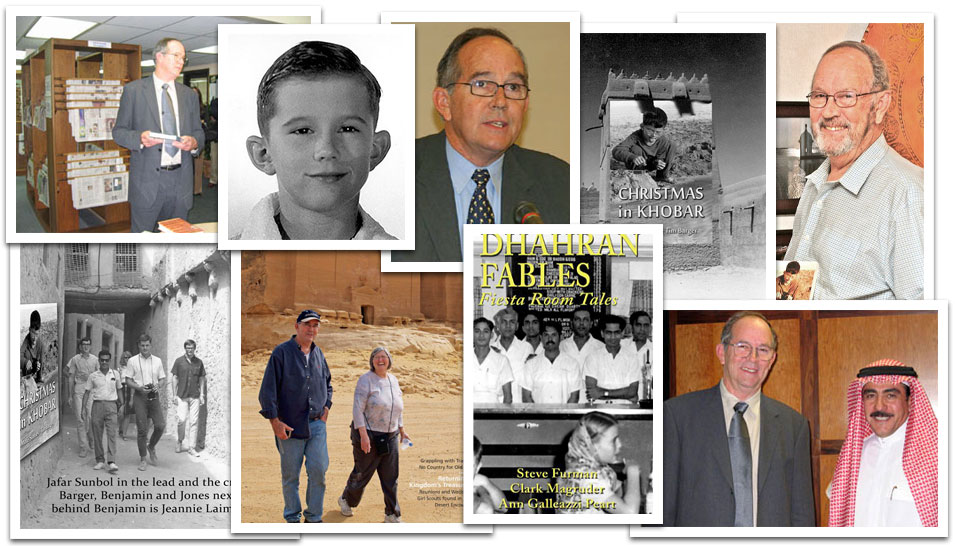

An Aramco “brat” through and through, Tim Barger was a prominent and much-loved member of the Aramco family—a motive force in fostering goodwill and better understanding for the Kingdom, its enterprises, and its people. Tim passed away at his home in Vista, California on the 15th of this month at the age of 70. Yet, the contributions he made and the example he set will endure. We who once knew him mourn his loss, but we also celebrate his life and give thanks for having had the privilege of calling him a friend.

Tim was born to Thomas and Kathleen Barger in Dhahran on 18 September 1947 and continued to call the Kingdom home until age twenty-one while attending high school in Wisconsin and college in California. A gifted writer, he is best left to tell the story of his family’s early years in Arabia himself in his own words:

“My father went to Saudi Arabia in 1937,” Tim recalled in an interview. “He was one of the first dozen geologists to go into Saudi Arabia and see what they had in their concession. The men knew nothing about Saudi Arabia; they barely knew where it was. They took a motor launch from Bahrain over to al Khobar. The first thing he saw was the camps. … There were two giant tents and about 5,000 Arabs with knives and guns and rifles and swords and all kinds of tribal weapons. The occasion was the visit of the Crown Prince of Saudi Arabia, Saud bin Abdul Aziz, and he had come to meet the Sheik of Bahrain."

“The political significance was, the Sheik of Bahrain was already pumping oil and that Abdul Aziz and his son Saud hoped that soon they would be pumping oil. But by then, still, they didn’t have any oil. They had drilled something like ten dry wells, and they were losing faith. … They had one more well in production—well, not in production, they were drilling it—and basically, if they didn’t find any oil they were going to close down the concession. So, my father arrived, and about a week later he went into the desert for three, four months (and) lived with fifteen Bedouins."

“He really got to know Bedouins and Arabs. They had nothing to do but run around all day and talk and chat all night long around campfires and that kind of thing. And so my father real quickly learned Arabic and got to know these men. And he thought it was terrific, because these men, they weren’t changed. I mean that, except for gunpowder and raw sugar, they were living like Moses lived. I’m telling you all this because that’s where my father figured out what was going on in Saudi Arabia."

“He was a junior geologist at the time and, later in his career, he rose higher and higher until eventually, he was the CEO. But throughout the whole process, he always knew who those Saudis were. They were not foreign people, they were real people that he knew heart to heart. And I think that’s what distinguished his whole career. Whenever there was a conflict between a Saudi employee and the company, ninety-nine percent of the time my dad went with the Saudi because he understood what they were trying to do."

“So, while he was doing that, I was growing up. When I was about six I think that Dhahran went to about tenth street then, and after that, there was nothing between Dhahran and Al Khobar. There was no fence, and you’d wake up in the morning and jackals would be roaming through town. I mean, it was pretty wild. But as a kid, it was absolutely terrific because you’d just (head) out the door and into the desert with all your buddies and get into all kinds of trouble and run around. It was fantastic!”

Throughout his life, Tim was noted for his kind and gentle sense of humor, which he often directed at himself as he shared stories from his life in the Kingdom:

“There is stupid,” he once wrote, “and then there is another category even dumber than stupid. At seventeen, I was pretty much the poster child for beyond stupid though it wasn’t entirely my fault. I was more than six feet tall, weighed maybe 170 pounds, and had the body fat of a praying mantis—except for that gram of fat on the pathway between my frontal lobe and my cerebral cortex.”

Despite whatever body fat he may have had clogging the pathways of his brain and hindering rational thought, Tim learned valuable lessons from his father, as evidenced in a speech he delivered to an audience in Saudi Arabia in 2008 gathered to celebrate the seventy-fifth anniversary of the founding of the company:

“Today we celebrate Saudi Aramco’s seventy-fifth anniversary,” Tim remarked. “It is a remarkable achievement and a success beyond the wildest dreams of the king and the men who set it in motion. It is well worth celebrating, but it is also good to remember that there was nothing easy about building this company. Starting from scratch in 1934 —less than a year after the oil concession agreement was signed—geologists Burt Miller and Krug Henry pitched a few tents in the shadow of Jabal Dhahran and laid the foundations for this great company. …"

“Because we come from different cultures, we do have differences. But, like friends, we focus on what we have in common, and the similarities are so much larger than our differences. … I am just one of the many Americans who have lived in your country for years. There are more than a thousand Americans working for Saudi Aramco right now, and there are tens of thousands who have worked for the company over the past seventy-five years. There are many thousands of us who were born and raised in the Eastern Province. We are not Saudi-Americans, nor are we American-Saudis. Maybe we are Saudi Aramcon-Americans!"

“Regardless of the name, I thank all of you Saudi-Arabians for your friendship and for generously accepting us within your society, for teaching us about another way of life, for sharing with us the beauty of your country. But most especially, I thank you and your parents for respecting the achievements of our fathers. They did their very best to help make Saudi Aramco the success that it is today, and we are very proud of them and their contribution—as we are of this great company. On behalf of these Americans—past and present—I’d like to say, “Nashukraan jazilaan.” [شكرا جزيلا] (Thank all of you very much).”

Tim’s parents, Tom and Kathleen, met while students at the University of North Dakota and married after she graduated in 1937, a mere two weeks before Tom was scheduled to depart for Saudi Arabia. His new bride planned to join him in the Kingdom the following year, but first a severe housing shortage in Arabia and then the outbreak of World War II delayed her arrival until early 1945. That year, with war still raging in Europe, Kathleen, along with a group of other wives, arrived in Cairo by ship and flew from there to Dhahran. In that fast-growing settlement, she and Tom lived together for the next twenty-four years. In September 1947, she gave birth to Tim, third of their six children, the others being son Michael and daughters Ann, Mary, Norah, and Teresa. In 1969, Tom retired, passing away in 1986 in San Diego, California at age seventy-seven. Kathleen preceded him in death in 1971 at the age of fifty-four.

Tim attended college at Santa Clara University, graduating in 1968. In 1974, he moved to Riyadh, where he worked at the King Faisal Specialist Hospital, establishing the facility’s five-channel TV system, leading a team of twenty-eight employees, and producing and directing training videos for hospital staff. In 1977, he established SAEECO—the Saudi Arabian Electronic Equipment Corporation—providing technical services for video and cable television systems in the Jeddah area.

Together with his late wife Sydney, Tim founded Selwa Press, dedicated to publishing books centered on life in Saudi Arabia. Tim acted as editor and publisher for Out in the Blue: Letters from Arabia 1937 to 1940, based on letters written by his father to his mother recounting Tom’s many adventures working as a junior geologist prospecting for black gold in Saudi Arabia in the primitive, pioneer days of oil exploration in the Kingdom.

In the ensuing years, Tim authored two collections of his own stories of life in Arabia: Arabian Son: 21 Stories in January 2014 and Christmas in Khobar: More Stories in September 2016. Tim also published a novel, Pamela’s Song: Love, Loss, Rock & Roll, in 2012.

Scores of stories written by Tim have appeared on the Aramco ExPats website. You will find links to those stories if you enter “Barger” in the search box found above.

Tim’s generosity toward Aramco ExPats (AXP) and our readers was exceptional. Not only did he freely share his stories, but for fifteen years right up until his death he provided us with a steady stream of vintage photographs of Arabia, many of them gleaned from his father’s treasure trove of images dating from the ’30s, ’40s, ’50s, and ’60s.

Readers will find two videos dating from 1939 provided to AXP by Tim to be especially interesting. The first, shot in May of that year, captures on film the loading of the tanker D. G. Scofield with the first shipment of oil to be exported from the Kingdom. King Abdul-Aziz personally appears in the video, where he is shown helping turn the control valve to send crude flowing onto the ship.

The second video, dating from July of that same year, shows Saudi and American workers desperately fighting a raging fire at Dammam #12 that killed six men and threatened the very survival of the company until it was finally tamed ten days after disaster struck.

“The oil men quickly realized that not only the well itself but the entire Dammam field was at risk,” Tim wrote of this event. “Burning eight thousand barrels of oil a day, the well was lost. But if the blowout continued, the whole field might lose reservoir pressure and the oil would have to be pumped out at great expense. With no outside expertise or fire-fighting equipment available for at least a month, the oil men, resourceful veterans of overseas oil camps from Venezuela to Borneo, decided to extinguish the fire themselves.”

The footage provided by Tim and posted on our website is stunning. It portrays what Tim considered one of the pivotal moments in the history of Aramco:

“Watching this video, you can get an idea of the terrible conditions the oil men faced. It’s July in Dhahran, so the daytime temperature is already 120 degrees, and the conflagration makes it even hotter. You can see the men working the hoses as they approach the fire, and then the wind shifts to push them back with an invisible wall of unbearable heat. When the wind stops they surge forward again. Dozens of men are working the fire hose but notice the two men at the nozzle. Wearing no protective clothing except gloves, the American in a felt hat and the Saudi in a ghutra, maybe soaked in water, lead the attack on the flames. They are both there voluntarily, fighting together against a common enemy that equally threatens their livelihood. This may well be the defining moment in the early history of Aramco."

“The Americans and the Saudis were so disparate in language, culture, religion, and customs that the only chance they had of possibly working together was to set their differences to the side and co-operate. … When #12 burst into a furious, howling hellfire, the Saudis quickly realized what a threat it was to their families and their growing society. And for more than a few of the men at the front of the hose, men just learning about the oil industry, it was maybe more than that—it was about the pride of being an oil man with a job to do."

“Ten days later, the screaming flames went silent. The Americans retreated to their bunkhouses, the Arabs went home, and Aramco would never be the same. Daniel Yergin, the Pulitzer Prize-winning author of The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money and Power, once observed that the success of Aramco was only made possible by the quality of the people in those early days and their meeting of cultures. Seventy-five years ago the two cultures were welded by adversity into a third culture, an Aramco culture that celebrates its Diamond Jubilee today.”

Tim Barger was a unique, one-of-a-kind, sui generis individual as well as a familiar, archetypal, quintessential everyman. He stood tall in height and reputation for his unmatched generosity and fellowship and wisdom. Yet, to we fellow members of the Aramco family, he was more than that: He was a part of all of us, a brother in spirit if not in blood. Let us remember this fine man and keep the beacon shining brightly, one his father, Tom, helped light and Tim, a proud son, helped maintain.

For anyone wishing to make a contribution in memory of Tim, the family suggests making donations in his name to Doctors Without Borders at: www.doctorswithoutborders.org.