[At the conclusion of the previous installment in this series, our doughty band of Aramcons had just made camp for the night after completing a spine-tingling run through the most treacherous stretch of the Grand Canyon of the Euphrates, a series of rapids known collectively as the Serpent’s Mill. We pick up their story there, again speaking in the voice of AXP president Vicci Turner.]

***

Occasionally in this series, I’ve referred to the Euphrates in the feminine as in “her” or “she,” not, as most writers do, in the neutral as in “it” or “its” or in the masculine as in “him” or “he.” I’ve consulted Richard Bangs, past conqueror of the Euphrates itself and recognized expert on the general subject of rivers around the world, scores of which he has personally rafted, regarding my decision and he supports it.

In 2012, having received an inquiry from a Texas journalist, Susan Farlow, Bangs answered her back. In an article Farlow wrote for the San Antonio Express-News titled “How rivers get a gender attached to them,” she shared his response:

If anyone knows about the souls of rivers, it's Richard Bangs, an American and a legendary international river explorer who has authored 19 books, a score of documentaries and over a thousand magazine articles.

When I first contacted Bangs, he emailed that he was in Bosnia, rafting the “female” Una River.

So why is the Una “female?” Because, says Bangs, “it is mostly a lovely, winding, sensual stream.”

Often called the father of modern adventure travel, Bangs later wrote me, “Many (river) names are indeed attributed to gender, often because they remind the explorers or settlers of human characteristics attributed to a gender.”

Bangs went on: “Virtually all rivers were named by men. Very often, if a river is mighty, overpowering, dangerous, it is male,” such as the Tigres [sic], named for the male Tiger. On the other hand, “if it is gentle, curvaceous, easy on the eyes, it is often female.” Take the case of the Mekong, “which means ‘mother of all rivers’ as it births and feeds many of the great ... waters of China.”

But things aren't always so simple. And Bangs noted, there are no hard-and-fast rules about river names and genders. Names “vary by culture, geography, history, discoverers, and characteristics.” Moreover, he added, “many river names have no gender at all,” such as the mighty Nile, considered the world's longest river, at 4,130 miles.

Etymologists tell us that Euphrates is a Greek word consisting of two elements, the first part the Greek adverb ευ, meaning good, well, or noble, the second part a transliteration of the river’s Hebrew name, פרת (Parat), derived from the Hebrew verb פרה (para), meaning to be fruitful. Thus, in English, the Euphrates’ name translates as “good and fruitful.” In any language, those are decidedly feminine traits.

I look upon the Tigris and Euphrates rivers as fraternal twins, as brother and sister respectively, each alike in so many ways yet each with its own distinctive character. At times, the Euphrates could be soft and sweet, curvaceous and alluring in stereotypical female fashion; but that only served to disguise her true character on display in Serpents Mill, home to Scylla and Charybdis and hot springs near Tilek. Initially seduced by the Euphrates’ softer, siren, Lorelei side, Bangs and his companions nearly died when they encountered her turbulent, fierce Scylla persona. While our own experience was likewise death-defying, we had the advantage of knowing what to expect beforehand thanks to Bangs and Sobek. Without that foreknowledge, we might well have ended up as victims, not survivors.

***

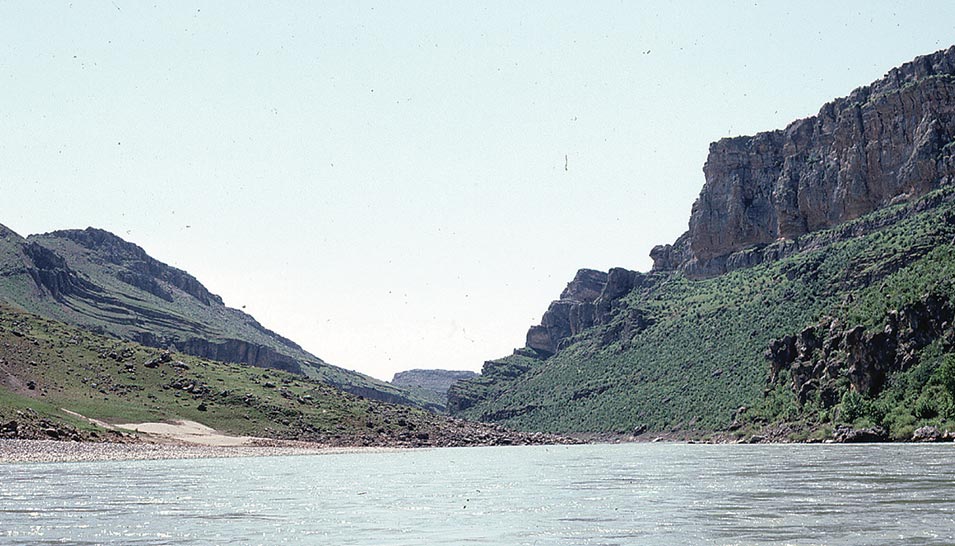

Moments of piercing terror were interspersed with others of astonishing beauty that day, for not every foot of the Serpent’s Mill of the Kemer Khan was comprised of rapids. At certain points, the Euphrates slackened her pace, however briefly, and more than once her canyon walls opened wide on one side or the other, revealing verdant valleys flanking secondary streams. At such moments, we caught glimpses of the rounded snow-capped peaks of the Taurus range looming in the distance, some as tall as 7,000 feet, a few rising even higher. There we sometimes spotted Kurdish women carrying water in long-necked clay jugs, as Richard Bangs described in his 1981 article for Saudi Aramco World. In scattered spots, farmers had carved out terraces from the canyon slopes—some of them impossibly steep—and planted crops, giving color and texture to the fabric of the land. Occasional stands of poplars appeared on river flats alongside where tributary affluents joined their Euphrates mother at river level, adding a largely-lacking sylvan element to a region where deforestation had mostly denuded the countryside of trees ages before.

To gouge out the dramatic gash in the Taurus Range through which the Euphrates flows, some titan-like figure—Atlas, most likely—in primordial times must have seized the mountains in his mighty hands and ripped them asunder, creating the deep, jagged, winding river canyon seen today with vein-like cracks knifing in from one side or the other at wildly irregular intervals. Through the ages, as rains fell and snows melted and waters flowed, the rough furrows first formed slowly assumed more refined shapes, transforming themselves into what had become by our time a variegated, crosshatched, nuanced web of feeder streams. They joined the Euphrates’ main flow from assorted heights—many at the river bottom, some a quarter- or half-way up the canyon walls, others somewhere in between or higher still. Thus was born the procession of veil-like waterfalls we witnessed as we drifted through the heart of the Kemer Khan. If the angle of the sun was just right when you looked their way, you were treated to rainbows in the mist.

According to Ellsworth Huntington—a titan-like figure himself in the field of geology—the Euphrates is a relatively young river measured in geological years. His evocative account of the Kemer Khan (the “Kemur Khan” in his spelling), Through the Great Canyon of the Euphrates River, informed by vast scientific knowledge, explains the origins and character of the canyon in more precise terms:

At Kemur Khan (where, notably, in April 1979 we launched our three Avons to start our descent of the Upper Euphrates) the river turns at right angles and goes south by east through a remarkably straight gorge 12 miles long and nearly 4,000 feet deep. The scenery is even finer than in the preceding gorges. The dark, steep, gloomy walls of basalt and metamorphic shale are terraced at an elevation a few hundred feet above the river, and on each terrace or nestled in each tiny valley are one or two houses and a patch of bright green fields.…

Through the whole length of the gorge we went at an average rate of 5 miles an hour, between walls of solid rock which come down sheer to the narrow stream, and are broken only by precipitous gullies entering at grade and bounded by jagged cliffs with needle-like points. The mouths of these gullies are footed by fan deltas, which have been pushed out into the river, forming dams, over the outer ends of which the water pours in foaming rapids…

…The river, turning once more to the south from the longitudinal valley, enters an immense crooked transverse canyon (Huntington’s referring here to the Serpent’s Mill), the last and longest of the great gorges, 30 miles long and 5,000 feet deep. … Near Tilek the river turns more directly south and passes through magnificent scenery. At the bottom, schist, formed by the metamorphism of shale, forms almost perpendicular walls, which we estimated as nearly 400 feet high. Above is a terrace, from which green wooded upper walls rise less steeply to the mountain-tops a mile above our heads. The larger tributaries cut through the apparently perpendicular lower wall in steep-sided narrow canyons, entering the main stream at grade, while several small streams have not yet cut down to grade, and cascade over the cliffs in a series of white falls.

Huntington went on to compare what he saw on his descent through the Grand Canyon of the Euphrates to what he knew from having previously studied the Grand Canyon of the Colorado:

These hanging valleys and many other characteristic features of the Euphrates cañon (Huntington’s idiosyncratic spelling of canyon) correspond closely to what is described in the Grand cañon of the Colorado river, showing that the two rivers are of nearly the same age. The Colorado cañon is much longer than that of the Euphrates, and is cut through a plateau of nearly horizontal strata instead of through a range of mountains formed of much-distorted strata; but in both cases the depth of the cañon and the inclination of the walls, very steep at the bottom and more gentle above, are approximately the same. Both rivers are so young that they have not yet established thoroughly graded channels, but no waterfalls are found such as we should expect in extremely young streams. There are, however, the two kinds of rapids which I have already mentioned, viz. Those due to outcrops of hard rock which have been worn back so far as to present a regular but nevertheless very rapid descent, and those due to the damming of the stream by fans of detritus brought in by tributaries. It was by these that the famous journey of Powell down the Colorado was made so dangerous. We found that as a rule the bed-rock rapids are longer, but the fan rapids are more strong and dangerous. They indicate that the rivers are approaching, but have not yet reached the stage of maturity when the whole channel assumes a graded character.

The junction of the side streams with the main river is another interesting indication of youth. The majority, as has been said, enter at grade through narrow steep-sided cañons, but some of the smaller tributaries and a number of wet-weather torrents have not been able to carve valleys as rapidly as the main stream has incised its cañon, and so have been left hanging at various levels on the cañon wall. … (They) send their streams cascading over the precipice directly into the Euphrates river, whose valley is so narrow that not only is there no flood-plain, but the water washes the rocky base of almost perpendicular cliffs. The Colorado river, it will be remembered, has just such hanging valleys where it passes through harder crystalline rocks.

Geologists estimate that the Colorado River has been hard at work carving out its Grand Canyon in the Southwest United States for 6 million years; if Huntington is correct in his observations, that means that the Euphrates River has been working every bit as long carving out a Grand Canyon of its own in far away Asia Minor. In both cases, the rivers have millions more years to go before either has completed its work.

***

A day after our unnerving do-si-dos with Hammerhead Falls and Turkish Delight, we arrived at a narrow point of the canyon referred to as Stag’s Leap by Helmuth von Moltke where work was progressing in the early stages of construction of the Karakaya Dam, completed in 1987 and estimated to have forced the involuntary resettlement of 30,000 people, including, I fear, Abdullah—the kindly shepherd who days before had provided us with goats milk and breakfast along with friendship and caring advice—and his extended family. Mike described the scene:

It looked like a great rock quarry. Was it a quarry? Surely they could have found rock somewhere less remote. We rowed closer. A huge diversion tunnel had been drilled through the solid rock of the north canyon wall. A Volkswagen could have driven through it. Huge squared-off vertical cuts had been blasted and hacked out on opposite sides of the canyon, the foundation truncheons for a reservoir. A temporary drivable bridge and a tall cable bridge vaulted the river. Heavy construction machinery gnawed away at the living canyon on both sides.

In a tense confrontation, armed Turkish soldiers wielding automatic weapons, alarmed by the unexpected appearance of a trio of crowded inflatables floating by, shouted down to us from the suspension bridge. Waving their rifles overhead like semaphore flags, they gestured for us to come ashore and explain ourselves. We just smiled, pretended not to hear, waved back, shouted “Merhaba!”—Turkish (and Arabic) for “Hello!”—and continued on our way, pointed south in the general direction of Syria.

I wonder still what was going through the minds of those flummoxed sentries as our modest flotilla paraded by, blatantly disobeying their orders, and what, if anything, they reported to their superiors. For all they knew, we could have been PKK terrorists on our way to wreaking havoc and death and destruction somewhere to the south. Violent bands of separatist rebels were, in fact, roaming those same parts of Turkey at the time—a reality we learned about first-hand a day later. Nobody had bothered to warn us of the danger Kurdish insurgents posed before we left Arabia, and none of us had been informed enough on current events in the country to think of asking. All we knew at the outset was that we had secured permission from the proper authorities for us to make the trip, and that was good enough for us, if not for those antsy guards. Recently, I learned a vastly different truth.

According to an account of our adventure written by Mike Ghiglieri decades later, the Turkish government never actually issued permits for our expedition. They’d answered Richard Bang’s written request for same with a resounding “No!” explicitly forbidding us from traveling to Malatya Province to raft the Euphrates. With our presence on the river that day, we were breaking the law—a problematic position to find ourselves in given the country and the time.

Six months earlier, the intense prison drama film Midnight Express had been released, graphically portraying the ordeal of a young American college student incarcerated in a brutal Turkish prison after being caught trying to smuggle hashish out of the country beneath his overcoat. Had we been arrested that day at that construction site and hauled before a judge—there are no juries in Turkish courtrooms—we would have faced a similar prospect. Pleading ignorance would not have helped.

Turkish law is based on the principles of Roman law, not on those of English common law like in the UK and US. Accordingly, in the eyes of Turkish law, a defendant is not “innocent until proven guilty” but rather “guilty until proven innocent” once charges have officially been brought against him or her. We were indisputably guilty as charged, only we didn’t realize it at the time. Once we were made to understand our true situation, our only defense would have been to plead ignorance and throw ourselves at the mercy of the court. Employing such a strategy offered no guarantee of success.

Ignorantia juris non excusat is Latin for “Ignorance is no excuse for the law.” Turkish law disdained the use of Latin phraseology, despite its adherence to the principles of Roman law, but no matter. Our judge would not have needed mastery of the language of Caesar to find us guilty. Had Turkish authorities discovered our ruse, our fate would have rested in the hands of powerful forces over which we had no control. We had survived the Euphrates; would we survive the Turkish legal system, or, even more frightening, the Turkish penal system? To our innocent, uncomplicated way of thinking, we were out for a lark and having fun—that, and nothing more. Had we known the truth that day, we likely would have felt differently; had we known the truth before we left the Kingdom, we might not have come at all. Ignorance is no excuse, but it can be bliss.

When Rusty and Brad reached their teen years and started doing the crazy, stupid, risky things teenage boys are genetically pre-wired to do, Ken and I sat them down and made them watch Midnight Express with us as a warning not to do anything too foolish as they traveled the world un-escorted by responsible adults as thousands of Aramco brats of similar age routinely have done for decades. Thankfully, they heeded the lesson, or at least managed not to get caught if and when they transgressed. Thankfully as well, nobody caught us in the spring of 1979 when, out of innocence and ignorance, we egregiously broke Turkish law.

[to be continued]